Scrolling Through the Past

One of the most effective formats of the Chinese ink-painting tradition is the handscroll. Handscrolls evolved out of ancient, largely practical, written texts on strips of bamboo, strung together and rolled up. They only began to emerge as a powerful pictorial format in the first millennium CE. Their sophistication embraces several facets of fully emancipated, fully efficient creative perception and expression – what we call ‘art.’

The handscroll breaks down the distinction between artist and audience, an essential feature of fully emancipated art. The viewer takes control of the ongoing process. Having finished the painting, mounted it as a handscroll, and presented it to the aesthetic world, the artist passes the baton of self-realization to the audience. Ideally, it is a solitary journey into the perception of the artist. Rather than being a spectator sport, as an exhibition of paintings hanging on gallery walls can become to the vast majority, it is a meditational exercise in uniting with the process of meaning through art. The viewer controls the temporal, formal, and psychological ongoing aspects of the experience, controlling the composition in a dynamic partnership with the artist – reflecting the ideal essence of communicating meaning.

The initial impulse for a neophyte is to unroll it to see what happens – ah, the baggage of Aristotle, Newton and Einstein – but this is not a format that is even partially grasped by the neophyte. That is the whole point of the handscroll. It doesn’t confirm an existing worldview, it enhances it. Once a handscroll becomes more familiar, and the surface concerns give way from the temporal to the psychological, its powers are revealed.

One aphorism that arose out of mind-surfing is pertinent here:

Never mind ‘what,’ that’s about things. Never mind ‘how,’ that about function. Never mind ‘when,’ that’s already history. Never mind ‘who,’ that’s incidental. Just start with ‘why.’ You’ll save yourself a lot of time.

Having dealt with the ‘what’ we can move on. Instead of seeing the process as fulfilled, i.e. the ‘what,’ we can immediately return, concentrating on a different inner language and discover an entirely different approach to the work of art – the ‘how’ of the handscroll experience. Immersed in the inner languages, their role in self-realisation begins to emerge, and we visually mind-surf onto the littoral of meaning. That is why the handscroll has intrigued me as a collector and artist, and why, as agent for some of the greatest expatriate artists of the ink-painting tradition, I encouraged them to return to the format with commissions and admonitions.

You can’t bounce off a handscroll the way you can bounce off a hanging painting. Many paintings, hanging in the same place for long periods are in danger of becoming functionally invisible as art; they are mainly revitalized through the eyes of visitors ‘Good heavens! Is that Van Gogh’s Irises, Mr. Bond?’ ‘Wow, I am shaken…and stirred!

***

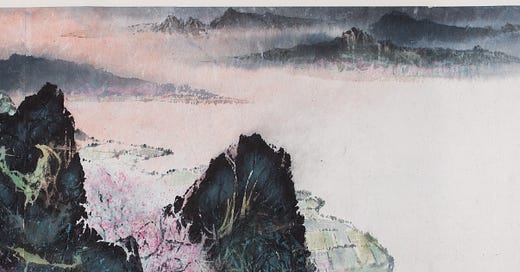

Liu Kuo-sung (Liu Guosong) - The Four Seasons 1873 (1983)

58.7 x 846.6 cm

Title Panel: An encomium by Li Keran, signed and dated to the Winter of 1984

Click here to zoom in on high-res image

***

Ho Huai-shuo - The Four Seasons (1984)

57.8 x 1,070 cm

Title panel: Jao Tsung-I (1985)

67.3 x 106 cm

After Liu Kuo-sung completed the Four Seasons handscroll, I showed it to Ho Huai-shuo who responded with his own version, which is larger, and, of course, quite different. Again, a blank title panel was later inscribed by the Hong Kong literatus, painter, calligrapher and scholar, Jao Tsung-I at my request at the suggestion of the artist.

Click here to zoom in on high-res image

***

The Master of the Water, Pine and Stone Retreat - Startling the Birds (2017)

27.5 x 183.5 cm

Title slip:

Startling the Birds. With one seal of the artist, 水松石山房 Shuisongshi shanfang (‘The Water, Pine and Stone Retreat’)

Title panel:

Startling the Birds.

Inscribed by the Master of the Water, Pine and Stone Retreat on a painting that kept me company around the world in the summer and autumn of 2017. With two seals of the artist, 水松石山房 Shuisongshi shanfang (‘Water, Pine and Stone Retreat’), and 養石閒人 Yangshi xianren (‘An idler who cherishes stones’)

Painting:

I'm idle, as osmanthus flowers fall,

This quiet night in spring, the hill is empty.

The moon comes out and startles the birds on the hill,

They don't stop calling in the spring ravine.

Wang Wei wrote these lines many centuries ago. Today I call him back to visit me in my studio by illustrating the poem and inscribing his timeless words.

Click here to zoom in on high-res image

For further writing on handscrolls including more high-res images of more favourites by Ho Huai-shuo, Chen Chikwan and The Master of the Water, Pine and Stone Retreat, visit transculturalink.com